Q: First, can you tell us a little bit about yourself as an artist and your artistic practice?

A: Hello! My name is Shawn, or Tronald—once known as Tron when I was 12 on the internet, but later given the name Tronald by a loving internet community: mIKes ReVeNGe, or mR. My practice is one of collage, in a sense, but also an exploration of digital tools. I like the act of transformation: through mediums, through placing things next to each other, through bringing things in and out of the computer, by changing old photos and reusing them. It’s like the use of personal archives with the addition of media, both new and old.

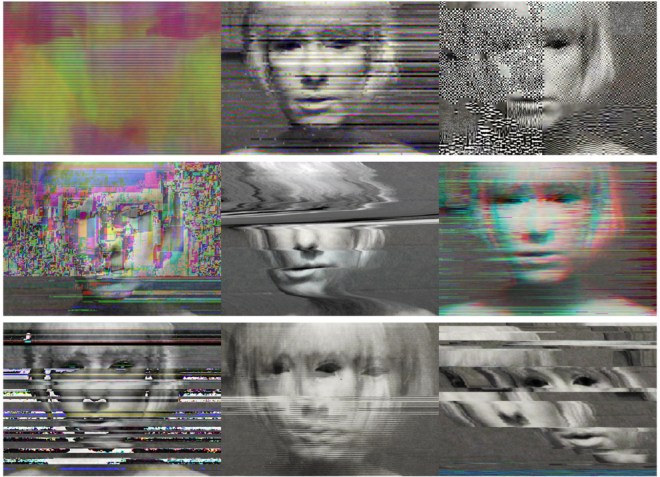

I often want my work to look constructed. I want the digital to be obvious. I do not want to hide the pixel… Some of the information has been lost on it. What you might be able to scan contains either short poems or phrases.

Q: What do you think are some of the key influences that led you to develop your artistic style and process?

A: You know? That’s hard. My 1st influences, who will always have a place in my heart, are my Alfred University friends. Following them, Rothko, Frankenthaler, Kandinsky, Newman, and the rest of the normal canon of colour field and abex painters. In my formative years as an artist, I was watching as many YouTube videos as I could find on art history and artists, now anonymous to me due to the amount of time that has passed. I can better describe the mindset that I garnered from these friends and artists. I didn’t know what skills I would need, but I knew this: I had to do my best to create freely, let go of feelings of failure, understand that there are hundreds of works left to be made, and commit to finishing a work despite its quality. One of the biggest influences was my ceramics friends at Alfred, not on just my art but my life. I’d see these people labor on their work only for it to fail at so many different points, and you know what they did? They would take 10 minutes tops (with a cigarette, depending on the person), walk out of their studio, then come back in like nothing happened and get back to work. That stuck with me.

That all said, it’s hard for me to point to specific visual influences, especially during my beginning years simply due to the fact of how voraciously I consumed art.

I can point to three non-visual artists and an author, however: AJJ, John Staurt Mill (I’m always surprised when I say that too), and Kurt Vonnegut. AJJ were originally a folk-punk band. Now, well… something different. I’ve been listening to them since I was a freshman in high school, and their lyrics range from anywhere from heartbreaking to touching to absolutely wackadoodle. Some songs sound like they just used all their intrusive thoughts for lyrics. But it’s the creative, sometimes disturbing, sorta placed-together imagery of their songs that stuck with me.

My brother suggested to me during my Alfred years that I read an essay by Mill. Misinterpreting him, I read his entire book On Education.1 This book helped me understand better how structures are fallible, how their self-bias grows over time, and accept the fact that I will always be at least a little wrong about things. Structures will cycle into other imperfect structures. Further, this book helped me understand something key to my dissatisfaction with traditional education: one is not allowed to learn how one learns best. They are given a learning model to follow, despite their wants and differing abilities. One learns how one learns best when they are allowed to follow their interests naturally, to make their own model. This is where a sort of obsession with structure and failure started for me.

Kurt Vonnegut is a relatively simple influence on me. His books got me reading, something I had never seriously done before. In his writing, he matter-of-factly and nonchalantly places people, things, and events next to each other. It’s absurd and serendipitous, but the way he writes it, it simply is.

It’s because of these influences it’s not unoften you’ll see other structures implied in my compositions that extend out of frame or are hidden or obscured in some way. I suppose there is something else I should mention: epicycles. When I learned about epicycles in physics, and how long and hard physicists of the time kept fighting for the theory… safe to say it’s worth looking into.

The last influence I can think of is dance. In my improv sessions, I can potentially reach a certain place in my imagination and have very strong visuals in my head, and I have used these directly before. See my works with a hand and googly eyes. Every creation in my life, my music, compositions, dance, writing, all speak to each other.

Q: As a multimedia artist, you employ a diverse range of both digital and analog media in your artwork. What got you interested in digital art, and does your creative approach differ when you work in digital vs. analog media?

A: After studying abroad, I realized I needed a change in the course of my life. When I went back to Alfred University, I took as many art courses as I could, one of which happened to be a digital drawing course that combined Photoshop and traditional drawing. Actually, I should note that I nearly didn’t go back to school. I almost dropped out. After that year, and in the process of transferring to Sarah Lawrence College, my brother, a 3D generalist, encouraged me to take online classes in 3D modeling. From there, I was lucky enough to have Shamus C as a professor in Blender 3D modeling.

I feel like one of my 1st loves in art were the media in and of themselves and how they mixed. I liked playing with phone cameras on full zoom where the pixels were obvious. On reflection, transformation was one of my main curiosities, not only between mixed media, but how images and information could be transformed when projected, when zoomed in on—how something can transform through a digital medium back out into the physical world.

I chose digital. I looked around me at my incredibly talented friends, these painters, sculptors, glass artists, ceramics artists, and I felt some pressure. There were many traditional foundational skills that went along with these media, and, though I was young, I felt time’s pressure. I saw digital media as something lacking traditional standards or foundations, something I could just start doing. I also chose digital media for this quality. It was fresh, new, unexplored, and constantly expanding. Everyone involved is still figuring things out together.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t come forward with the fact that my continuation in digital media is also due to economic considerations and space. It was a joy in college to work with wood, plaster, clay, cardboard, and metal, but those aren’t particularly realistic for me to work with, other than small-scale clay or cardboard work. With a computer, all one has to do is buy a nice one every few years.

So, does my approach differ? Other than my use of equipment, it has, but I’m not sure if it does these days. Everything I have made in the past year and a half has been in service of some final product with a clear goal in mind, for better and worse. I started figure drawing again and just drawing again in general very recently. I kinda just want to draw right now. I think a “freer” period is coming on.

Q: Can you expand on the role of memory in your artwork, both in terms of your artistic process and how you translate memory processes visually? Do visual mnemonic techniques, i.e., ars memoriae, play a part in either?

A: Specific memories have not yet been fully represented in my work. It’s kinda like if I took the structures of my memories and filled them up with other things as a remix of sorts. I more often respond to memories from time to time. My works, to me, are often “mixed spaces,” discordant things placed together. There are many reasons why I choose to do this. There is no pleasant way of putting this; one of those reasons that has to do with memory is the fact that, for a period of my life, I had to deal with flashbacks. I’d be sitting in a room in one place, and I might have been somewhere else. In a horror film, what’s the point of seeing the monster? You can lose so much when you say things out loud. There are good and horrible things, and their emotional content (truth?) and potency can be severely damaged by putting them plainly.

As far as how I translate memory visually, well. There are literal representations in my work in the way of photos, and I use them as backdrops to my compositions or use them as covers on 3D objects. Although, I think memory is more influential on my process and how I think about making. Something next to memory that also influences how I think: we all have our internal contradictions. We shouldn’t be afraid of those, nor the fact that we have many aspects of ourselves with loosey-goosey boundaries (or none, I’m not a professional lol). I guess your question has me quite focused on how much of our memories make us, and all I have to say in regards to that is I’m pretty sure we probably aren’t just a fishbowl of collected experiences.

Q: Your artwork is highly informed by your personal experiences, and yet it also conjures a sense of popular nostalgia. How do you navigate between the personal and the popular in your approach to image-making?

A: I’m not a particularly nostalgic person. Too much nostalgia is, like anything else, bad to debilitating. I think people read nostalgia in my work due to the use of warm colours, dreamlike scenes, and low-fidelity 3D models. My work is in part personal, but it’s also a response to popular digital/media culture—and that means, for me, using its aesthetics, which quite often can be nostalgic. In responding to such a day and age where nothing seems new and everything seems to be a callback in this never-ending loop of recycled content, it feels appropriate to appropriate some of that in my work. I mean, the end game of attention-grabbing algorithms is to find the perfect balance, to completely suck oneself in—mostly to sell you things or ideas. Maybe by providing an example I can help answer this question. I would like to mention first, for clarity, I am not anti-nostalgia. I think there is too much cynicism surrounding, well, actually everything, but also nostalgia. Anywho.

Let’s focus in on one part of Wildcat’s Apparitions. In large part, this work is inspired by a character in a song I found. When looking through the records on my grandmother’s Victrola my family inherited, I listened to “Don’t Fence Me In” sung by Roy Rogers. The character in the song was named Wildcat Kelly, perhaps an outlaw, or just a GUY who got caught up with damn Johnny Law. I combine this character with 2 infowar libertarians I regularly served at my retail job. Finally, the cowboy hat is recurring in my work, and this is where something more personal comes in: I grew up watching, like, every single John Wayne and Clint Eastwood movie plus a ton of other cowboy movies. The American Cowboy individualism is of great personal interest. Though the work didn’t start out in this way, it ended up being partly a libertarian fever dream in response to the uprisings happening that summer.

So it’s like, whose imagery am I working with? Whose time period? How is it meeting me? How do I think they are compared to the world we are living in, and how is it constructed? See the obvious photo backdrop? I often want my work to look constructed. I want the digital to be obvious. I do not want to hide the pixel. The photo on the houses is an old polaroid I took in… 2012? I mean, this is long-winded as is, but on the flip side, on the personal, as someone who grew up in a suburb, there is this feeling that climate change will not touch us, that rising fascist violence will not touch us, that we have the height of the American dream, and that we are the freest we can be. Suburbanites: tamed cowboys. There in the center, you have the shipping label drawn over, dissolved with hand sanitizer, scanned, then digitally manipulated. Some of the information has been lost on it. What you might be able to scan contains either short poems or phrases.

Q: On that note, what does art mean to you personally?

A: Well. That’s a big question.

Personally, it is the effort of taking my brain vomit and putting it together in a coherent way in hopes of communing with it and understanding it: if this doesn’t come to fruition then, at the very least, it was a practice in follow-through, and self-honesty, and disciplined effort. This is my art in the best conditions. I like learning things, I like putting things together; this brings me joy. But these days, I’m not really sure if understanding what you make is that important—in the moment or maybe even ever. I don’t know anymore. The effort to try to understand something can often be a hindrance to actually getting it.

Q: Congratulations on your first exhibition in VR, by the way! As a digital artist, do you see any potential applications for VR for exhibiting your artwork that would be unrealizable in traditional gallery settings?

A: Digital spaces can go as far as code can take them, and that’s pretty hecking far! In many ways, it feels like an equalizer. I mean, anyone can come and show up from anywhere. I can look at anyone’s work from anywhere in the world in an immersive environment. It feels like a great addition to a global internet community.

Q: What’s the latest project you’re working on? And where can we find you?

A: Animation! From time to time, I like to revisit animations that have elements that loop and don’t loop. And I’ve been drawing/sculpting in VR. I’ve also been playing with making 3d environments and treating my camera like, well, a camera. I set it up at one angle, compose, then set it up at a different angle and fill in the spaces. Occasionally, I make these different angles look like postcards, or magazine covers. I want these renderings to feel like different parts of the same world or a world next to it. I’ve been playing with freight crate imagery. You know? I don’t know what is next, and that’s okay. I’ll just keep making until the other shoe drops.

You can find me @Tronald_Charles on Instagram. You can also find me where I currently am, if you’re so motivated—if I don’t see you first, that is.

Shawn Bailey is a mixed-media digital artist whose work centers around the transformation and collage of images and memory through analog, chemical, and digital means, bringing subjects in conversation with their own histories in transformed contexts.

Shawn’s Solo Exhibition “Memento Loci” is currently on display in the LOAM.fun VR Gallery. Events with the artist will be scheduled for Art Gate International 2022, TBD.

※

1 John Stuart Mill, On Education (New York: Teachers College Press, 1971).