Seriality presents a challenge to the notion of value in contemporary art. This challenge is perhaps the most pertinent to digital and web art above all other media—what constitutes value, financial or cultural, in an endlessly reproducible medium to which everyone has unlimited access?1 Digital artists have introduced financial and artistic interventions that attempt to rectify the valuation gap between their art as art and their art as an informational commodity in an infinitely reproducible format. From NFTs to collaborative web art projects, this essay discusses the relationship between value and reproducibility in digital art.

Digital art’s online medium necessarily locates it on the same platform as mass media. However, by nature of its platform and technological format, digital art is also uniquely suited to exploring technicization.

Walter Benjamin explored seriality in relation to photography and film in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Benjamin proposes that while art has always been reproducible to an extent, a change occurred around the turn of the century when “technical reproduction had reached a standard that not only permitted it to reproduce all transmitted works of art and thus to cause the most profound change in their impact upon the public; it also had captured a place of its own among the artistic processes.”2

Mechanical reproduction caused a paradigm shift in the value and reception of works of art. Prior to the age of mechanical reproduction, an artwork’s value rested in its ritual or cult value, which was tied to its authenticity and aura.3 Authenticity requires the presence of an original work of art; it is “the essence of all that is transmissible from [an artwork’s] beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced.”4 Aura corresponds to an artwork’s “presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” and is connected to its embeddedness in tradition and ritual use.5

Technical reproductions diminish the aura of the original by removing the distance between the artwork and the viewer, divorcing it from tradition and thus from its original ritual use value.6 In the case of digital art, the illusion of distance is gone entirely. Viewers can bring digital artwork that bears the same appearance as the original file into their homes or with them on their commutes. As such, the “original” work of art and its specific temporo-spatial context is no longer a site of reverence. Instead of ritual value, the artwork now carries exhibition value, which depends on the art object’s availability to audiences and the viewing pleasure derived from it by the public. Benjamin associates this new mode of reception with collectivity and ‘distracted’ mobilization, in which he saw the potential for political manipulation.7 However, this mode of viewing also allows for a more open discourse between the public and the art with which it engages.

Technical reproductions also deplete the aura of works of art by disclosing the artwork as techne, as technical in its essence.8 Benjamin likened art in the serially reproducible media of film and photography to objects of mass manufacture. This comparison held true for many at the time, so much so that the postmodern art market had to invent new ways to create value in works of art produced using mechanical or technical media. For example, the art market often circumvents the lower perceived value of artworks made using mechanical or digital production techniques by reinscribing value through markers of difference and artificial scarcity.9 In doing so, they attempt to restage the authenticity of the traditional art object in the eyes of the viewer by simulating the sense of uniqueness associated with an “original” work of art. These sales tactics are commonly employed in markets for collector’s items such as trading cards and tend to invent value around the speculative worth of an item’s or maker’s cultural capital. The market for art in traditional media, on the other hand, tends to generate value around an artwork’s provenance and the verification of its originality.10

Digital art as it exists online is perhaps the most easily reproducible art form, allowing viewers to copy images exactly and immediately with the click of a button at no cost. Though it shares this reproducibility with film and photography, the way in which it is serial is dissimilar from goods of mass manufacture. Rather, digital art exists in the information age. It is thus more comparable to other forms of data online, such as webpages or memes, than it is to mechanically manufactured consumer products. Importantly, digital art’s reproducibility derives from its intangibility and its resulting ability to be present in many places and times at once. In other words, digital art has the most exhibition value of any medium, with few limitations on space, format, social context, or viewership.

Though the comparison to data can be reductive, the medium’s particular form of seriality is perhaps digital art’s most radical characteristic. Due to the medium’s reproducibility, artists can promote and disseminate their ideas freely and have them shared by the public without the same barriers imposed on artists exhibiting their work in institutional settings. Both the reproducibility and mutability of the non-physical medium also potentially allow for a more collaborative and interactive art-making process by permitting more people to add to and modify the existing artwork while keeping the original file intact, creating a more open discourse within the artwork itself.

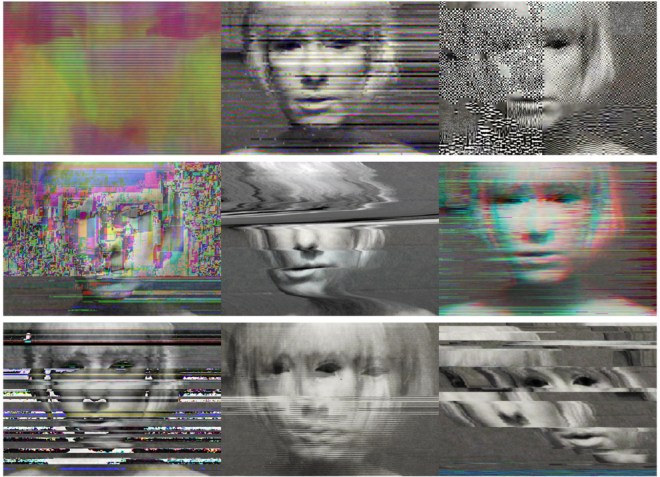

For example, Rosa Menkman’s A Vernacular of File Formats visualizes the mutability of file formats by compressing a single source image in different compression languages and then encoding the same (or a similar) error into each file (Fig. 1).11 In doing so, she exposes the otherwise unnoticeable compression language embedded in each copy, thereby illuminating the transformative power of reproducing and sharing digital images.12 Each reproduction has the potential to encode new meaning.

Digital art’s online medium necessarily locates it on the same platform as mass media. However, by nature of its platform and technological format, digital art is also uniquely suited to exploring technicization. According to Krzysztof Ziareck, “Entertainment, because of its technological hype, keeps us playing the game of technology, drawing us more and more into it to divert attention from the question of technicization; art, by contrast, makes technicization into the very question of its existence.”13 This is the crucial distinction between digital art and entertainment. It adds to the importance of art residing freely and accessibly on the same platform as mass media as a countershot to globalist power dynamics that otherwise determine the way information is organized in online settings.

For example, inspired by what he saw as the potential for dating apps’ predictive algorithms to influence human genetics, Harm van den Dorpel created Death Imitates Language (Fig. 2).14 In this project, the artist started a web platform that contained a large quantity of speculative works. He then made use of the web art medium’s reproducibility to ‘genetically’ program the website to generate new works of art from the existing files, each new creation inheriting sequences of information from its ancestors.15 The population is subjected to genetic selection via the artist’s input as well as the audience, whose engagement drives certain traits to live on and others to die.16 Once a work of art reaches its ‘optimal’ state, it is frozen and potentially translated into a physical copy.17 By leveraging the digital medium’s reproducibility and exhibition value to generate new forms, the artist creates the best possible version of the existing visuals. In doing so, he invents social and monetary value around the work of art, while also critiquing the technologized state of being in the information age.

Unfortunately for many digital artists, the discursive value of digital artwork does not always easily translate to monetary value or compensation.18 NFTs propose to remove barriers to profitability by reinstating the authenticity of the work of art through a direct connection to the artist, a new sense of ownership, and rarefication locating the artwork in a specific time and place. NFTs also renew a sense of private communion with the artwork despite the public accessibility of online art. Like with technically produced artwork on the postmodern art market, NFTs restage authenticity away from the “original” to unique copies. However, in doing so, they move towards a view towards art as a financial asset—a valuation practice representative of the established postmodern art market they problematize.

Much like with artistic prints, NFTs’ uniqueness is linked to differentiation in their production process. Artistic prints are made unique when the artist prints, signs, dates, and optionally numbers limited copies. NFTs, on the other hand, are made unique when they are minted, i.e., purchased. In other words, authenticity is manufactured in the print before it comes to market, while authenticity is manufactured in NFTs through the market itself.

While NFTs leave open the question of technicization and do not prohibit the circulation or modification of the image they tokenize, NFTs shift the discourse of the image to its purchase. They encode the tradition and provenance into the work of art by tokenizing the transaction between artist and purchaser. This link to the artist gives the purchaser the sense that the artwork is authentic, much like a signature would, and ties the artwork to a specific time and place. However, the once non-physical artwork’s objecthood and authenticity now derives from the event of the financial exchange inscribed in it. The NFT’s singularity, its thingness, is entirely a product of its having been sold.

YELLOW LAMBO by Kevin Abosch exemplifies this phenomenon by materializing the financial character of his work. YELLOW LAMBO is a ten-foot-long yellow neon sign containing 42 inline alphanumerics representing the blockchain contract address for the artist’s earlier cryptographic token YLAMBO (Fig. 3).19 The Lamborghini is an aspirational status symbol for a large community of cryptocurrency traders who use “#lambo” to represent their quest for profit via their crypto-investments. This sculpture commemorates the sale of the artist’s NFT inspired by this phenomenon, embracing the transactional nature of his art as a form of empowerment, if in a self-parodic manner.20 YELLOW LAMBO sold for $400,000 in 2018, more than the price of a yellow Lamborghini.21

This is also complicated by the fact that part of the financial value of NFTs is due to their free reproducibility as images and files online, which allow them to circulate and accrue reputational capital.22 NFTs of memes such as Nyan Cat are valuable because they are memes, not despite it. Likewise, it is unlikely that Beeple would have gained such prominence selling NFTs had he not made his work freely and publicly available for years on his own website and social media channels. NFTs are valuable in part because they rely on this reproducibility against which their singularity is compared. They highlight the fact that “While a digital artwork – like any digital asset, such as a synthetic derivative – exists only as bits of code, the ‘thingness’ of the work derives from the perception of its ‘value’ conveyed through the socio-technical apparatus the work is embedded in.”23 At the same time that NFTs invent new models of authenticity and ownership that more accurately reflect the lives of works of digital art, and the prerogatives of digital artists, they also center the thingness, the being, and the coming into being of the work of art in its financialization.

Sarah Ganzel is a New York-based graduate student of art history and curatorial studies as well as the Curator of LOAM.fun Gallery in VR. She has a background in medieval Icelandic studies and philology, and she is currently interested in exploring new critical approaches to everything from illuminated manuscripts to NFTs.

※

1 This essay discusses digital art that exists primarily online and on computers.

2 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schoken/Random House, 1969), chap. Ⅰ.

3 ibid., chap. Ⅳ-Ⅴ.

4 ibid., chap. Ⅱ.

5 ibid., chap. Ⅱ-Ⅲ.

6 ibid., chap. Ⅱ.

7 ibid., chap. Ⅳ-Ⅴ; Krzysztof Ziareck, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Electronic Mutability,” in Walter Benjamin and Art, ed. Andrew Benjamin (New York: Continuum, 2005), 219, https://www.academia.edu/8021831/The_Work_of_Art_in_the_Age_of_Its_Electronic_Mutability.

8 Ziareck, ibid., 214.

9 Rachel O’Dwyer, “Limited Edition: Producing Artificial Scarcity for Digital Art on the Blockchain and Its Implications for the Cultural Industries,” Convergence 20, (2018): 4, DOI: 10.1177/1354856518795097.

10 Laura Lotti, “Contemporary Art, Capitalization and the Blockchain: On the Autonomy and Automation of Art’s Value,” Finance and Society 2, no. 2 (2016): 103, doi:10.2218/FINSOC.V2I2.1724.

11 “Order and Progress,” Rosa Menkman, beyond resolution, accessed June 10, 2021, https://beyondresolution.info/ORDER-AND-PROGRESS-1.

12 ibid.

13 Ziareck, op.cit., 218.

14 “Death Imitates Language,” Series, Harm van den Dorpel, accessed June 7, 2021, https://harm.work/series/death-imitates-language.

15 “Death Imitates Language online genealogy,” Work, Harm van den Dorpel, accessed June 7, 2021, https://harm.work/work/death-imitates-language-online-genealogy.

16 ibid.

17 ibid.

18 For the same reasons it has such high discursive value, no less.

19 “YELLOW LAMBO (2018),” Studio Kevin Abosch, accessed May 22, 2021, https://kevinabosch.com/generative.html.

20 Studio Kevin Abosch, “YELLOW LAMBO (2018).”

21 “Kevin Abosch,” SOMA, accessed May 22, 2021, http://www.somamagazine.com/kevin-abosch/.

22 Lotti, op.cit., 103.

23 ibid.